Getting Into Poetry

By Rose Lindsey

For a number of readers, poetry might feel like a strange realm, unbreachable without knowing the forms and tricks inside-and-out. Despite being regarded as the “universal language”, new readers can oftentimes feel stranded without a way to navigate poetry’s contents and conventions. Thankfully, there are an innumerable poets in the world, and many provide a great opportunity for dipping one’s toe into the world of poetry. Today, let’s analyze the form and effects of a poem by one such poet who can help us “get into” poetry: Larry Eigner.

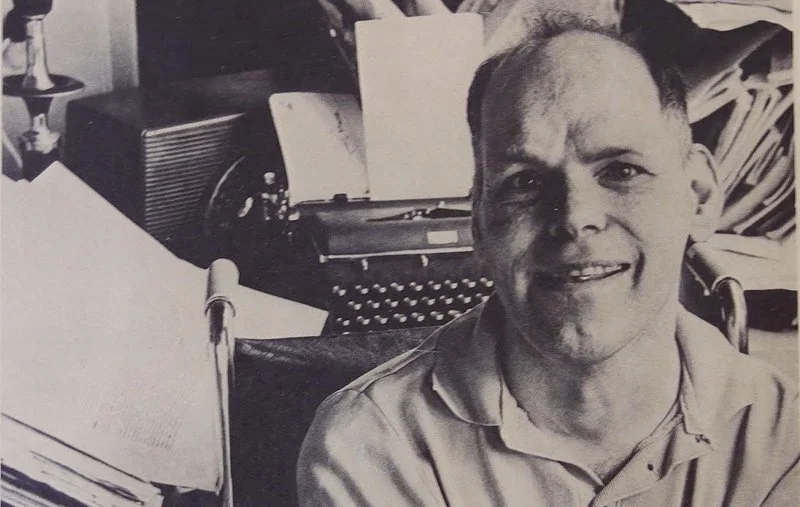

Larry Eigner was born in 1927 in Swampscott, Massachusetts, roughly 15 miles away from Boston. There, he lived with his parents for the majority of his adult life, until later moving to Berkeley, California in 1978. Eigner was born with cerebral palsy, which meant that he used a wheelchair throughout his life, and he was not able to lift a pen to write. Instead, Eigner focused his attention on the typewriter – a tool that did not inhibit him in any way. If anything, it gave him more control over the spatial craft of his poems.

Eigner wrote and published over 40 poetry collections in his life, a remarkable feat for any poet. His writing focused on observation of the world, primarily in regards to windows he looked through. Despite the straightforward images of his works, the language and form create experiences that feel contemplative, melancholy, or nostalgic – profundity in the mundane. How did his works achieve this? To answer that question, let’s look at a poem titled “File”, published in 1964:

On first read, one of the most striking qualities of this poem is its spatial arrangement on the page. There is a lot of interplay with white space, the areas of the page where words do not fill the emptiness. We also see examples of what could be called caesura, breaks in meter within the lines created by this white space (consider the wider space you see after “What of it”). Enjambment is also heavily utilized in this work, when the idea or phrasing runs into the next line without punctuation to indicate a stop. While these technical names can be helpful in discussing the poem, what is more significant than their formal name is what effect they have on the reading experience.

For instance, consider the second line of the poem:

“What of it we may be blown to the moon next week”

What if, instead of this phrasing, the second line was instead written to read:

“What of it? We may be blown to the moon next week.”

What changes about interpretation between these two phrasings?

When working with white space, a major consideration for poets is the feeling of leaving space for words to echo or for there to be words unwritten. Many times, the goal is to create an effect where the reader is able to fill the space with meaning, based on their own reading. This makes the question of “What of it” feel more “open” to the audience, as opposed to being closed-off by a question mark. Caesuras (the wider spacing) can also be used to create more distance between phrases, without completely separating the ideas with punctuation. If a question mark is added to the end of “What of it”, the phrase does not so easily flow into “we may be blown to the moon next week”. There is a particular movement between ideas that is important to Eigner in this line.

The use of caesuras and white space also lend themselves well to Eigner’s observational style. Line 7’s “it is raining, the hot metal smells wood” demonstrates this very well. Eigner is observing how the hot metal smells, and then is observing the sight of wood. Neither of these images are disconnected from each other, even if they feel in contrast, because they are both essential components of what the poet is experiencing at the time of writing. Separating them with punctuation would cause a greater separation of images as a whole.

For me as a reader, the most catching moment of the entire poem is line 14, which simply reads “moment”. Notice its spacing on the page, where there is a line break above and a line break below. The word is completely isolated on its own, feeling as though it is in suspension. The line catches you in its… moment. This is what can be described as the form performing the content. What I mean by this is, the word “moment” sits by itself and requires the reader to spend a second with it. Therefore, the word “moment” creates a moment within the poem – the form of the line directly mirrors the meaning of the word. This is a common technique in poetry, and can be used to embellish the sensations of reading.

That’s a lot of theory talk, but what effect does this have on the reading experience? We can look at the content of the poem itself for answers. The vast majority of Eigner’s work is reflective, but this piece is more explicitly in a reflective mode. Eigner is writing towards a feeling of contentment or satisfaction with the life he has lived. Line 3’s “All I’ve done is due to my limitations.” speaks to this feeling; by this time, Eigner had already published a number of poetry collections, and had found a particular meaning for his life in the typewriter. He lived with very direct, literal limitations on what he could do, and he still developed a life that was impactful for himself. “we may be blown to the moon next week” in the face of threats of war and violence, but for Eigner, “I don’t care if big cars come down off the trees”. Heavy machinery and artillery could descend, and if they did, Eigner would not die with regret. As a poet who wrote in an observational, meditative perspective, ending the poem with “life goes on in passing” is one of the most powerful declarations he can make. He has learned to appreciate and write towards what passes, what changes, especially in the outside world. The sights of the sky, the smell of the metal, these images are all of the moment of writing – and Eigner is satisfied with exploring moments.

The use of formatting in “Files” works to accentuate Eigner’s appreciation of the passing moment. The lines without punctuation create a more “fluid” reading experience, where the reader will easily pass from line to line. This creates the effect of the poem itself being a passing moment. We move through the writing simply, in a flow… and then it is over. As expected, Eigner’s poems commonly create this experience of a passing moment.

The ending also accomplishes what I would describe as echoing out from the page. Consider that there is no period to “contain” the final line. Instead, there is little white space that follows it. Whenever I read a poem that has an uncontained ending, it signals to me that the final line continues away from just this moment on the page. It echoes out. “life goes on in passing” is a truth that resonates for Eigner further than just this current moment, so why contain it to just this poem? The open ending is used in poetry fairly often, and even sometimes in novels, where the final line of the book is “incomplete” or “unsaid”. Ultimately, this effect leads the reader to consider the final line after the poem itself concludes – it creates an echo, or a resonance.

A final piece of content I want to emphasize is Eigner’s willingness to face contradiction. In line 6, he writes that “It is night and morning”; lines 8 and 9 share that “The truth, entirely exact, / is a contradiction”. Oftentimes, contradictions are seen as obstacles in the face of writing, and that a certain truth needs to be delineated. A beautiful aspect of poetry is that it reflects our experiential, human selves – and our lives and feelings are constantly filled with contradiction. Our experiences are never so easy as to not be complex. There are writers who will speak towards facts and certain knowledge, but poetry allows us to unshackle from the empirical sense of what is “real”, and instead explore what is seen, felt, held, personally known. Embracing whatever the experiential self is yearning to say is one of the most effective things a poet can do. Even with observations that feel direct and clear-cut, without many metaphors to latch onto, Eigner is a poet that succeeds in this through channeling the feelings of the moment into his formatting choices.

Hopefully this analysis has helped to broaden a sense of how poetry works, what techniques can be utilized, and what effects those techniques can have on an audience. Larry Eigner is one of multiple poets that have given me great inspiration in my work, and perhaps his work can inspire your own. Feel free to see how other poets utilize the formatting on the page, and experiment with it yourself. It is one of the key components to a powerful poem.